@sholum

>I am confused with this. English doesn't use the pattern of <sy> or <ty> to describe a sound anywhere near the pronunciation of those Japanese sounds; <sh> and <ch> are.

It doesn't, because English spelling does not reflect pronunciation; <gi> in English is also very often not pronounced as in Japanese but as in the English word "ginger", but the actual sound occurs in English.

Wanting to introduce segmental orthographical conventions from English is silly when things like <hy> or <ky> already exist in

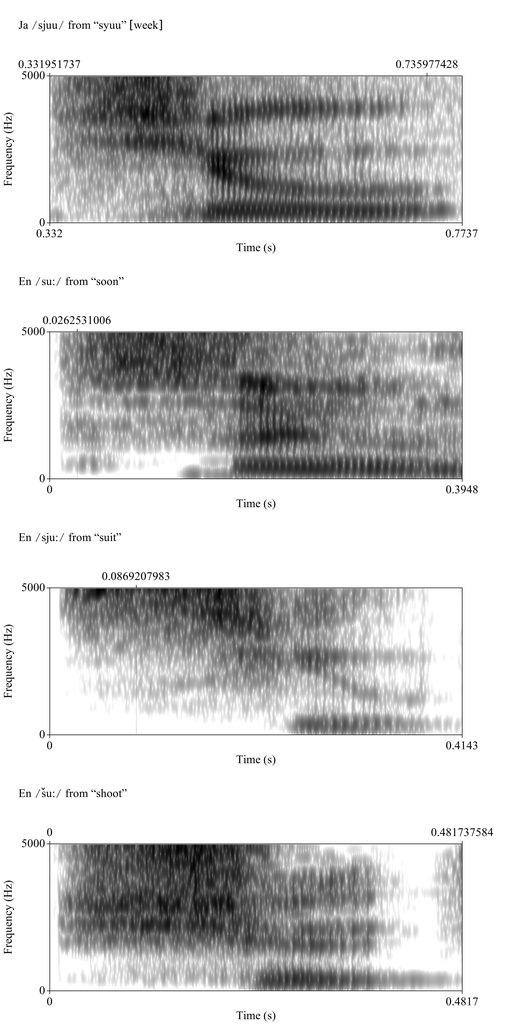

Hepburn Romanization which also do not occur in English. If it can handle <hy> to indicate the pronunciation, it can also handle <sy> which indicates the actual pronunciatio; <sh> is simply a mispronunciation. "suitable", pronounced "syootable" and "shootable" mean two different things and the <sy> row in Japanese is pronounced like the former, not the latter.

>Either way, though, 'assume' is still not spelled with 'sy'.

Neither is "cute" spelt <kyoot> in English, but it is still pronounced that way, so why not the same objection against

Hepburn's <ky>? the <ka> orthography is very rare in English, it is almost always spelt <ca>, why not do that too then if your goal is simply to mirror English orthography, not indicate pronunciation.

>In standard Japanese (I won't speak to any other dialect, but for a bias reference, most of the time I've spent in Japan has been in Nagano and Okinawa), し does not sound like 'si' as a rule.

Indeed, but it doesn't sound like "shi" either, as I said, it sounds like "syi" in general, but can also sound like "si", especially when raising one's voice, because Japanese does not contrast i/yi (or e/ye) phonemically. It is however never pronounced "shi", the sound of English "sh" simply does not occur in Japanese, at all. The vowel /i/ in Japanese is typically pronounced like "yi" when following a consonant, especially coronal ones, and "i" otherwise.

>This famous problem... It's neither sound. It's a sound that isn't really used in English at all

Actually it is a sound that occurs in English; it is in fact very often the same sound that many North American speakers make when pronouncing a "ẗ" or a "d" in between two vowels. Thence Japanese speakers tend to hear their version of /r/ when North-American speakers pronounce "pudding" giving "purin" but when other speakers do they her "pudingu"

>I think it's best to avoid putting consonants together when romanizing Japanese for English speakers (with exception for 'sh', since that represents a single sound);

And that is misleading, because it is in fact two sounds. か is to ikt as さ is to しゃ so why is <kya> acceptable, but not <sya>?

>And the 'z' sound in English doesn't show up in じょ

But it does, じょ is pronounced "zyo" after a vowel, and "dzyo" otherwise. As in is pronounced how in British English "presume" would be pronounced, as in "prezyoom", which is not pronounced "prejoom".

>With regards to pronunciation similarity in general; people will still screw it up regardless of the system

Which is exactly why I think a pronunciation-based system opposed to an orthography-based system is fruitless. But Hepburn in many cases isn't even a good pronunciation-based system that transcribes how it sound be pronounce — it is in fact further from that in many cases, because Japanese orthography is fairly phonemic.

>But you can limit the range of the error by using familiar structures.

Not if those structures repræsent different sounds. しゃ in Japanese is pronounce "sya", not "sha", "sh" is one sound, different from the two sounds "s" and "y" in succession, which is what the segment is in Japanese, and there are words in English that are contrasted by only this difference like as I said "suitable" vs "shootable", the former pronounced "syootable" and sounding different from "shootable".